Olive Trees Were First Domesticated 7,000 Years Ago

Earliest evidence for cultivation of a fruit tree, according to researchers.

A joint study by researchers from Tel Aviv University and the Hebrew University unraveled the earliest evidence for domestication of a fruit tree. The researchers analyzed remnants of charcoal from the Chalcolithic site of Tel Zaf in the Jordan Valley and determined that they came from olive trees. Since the olive did not grow naturally in the Jordan Valley, this means that the inhabitants planted the tree intentionally about 7,000 years ago. Some of the earliest stamps were also found at the site, and as a whole, the researchers say the findings indicate wealth, and early steps toward the formation of a complex multilevel society.

The groundbreaking study was led by Dr. Dafna Langgut of the The Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology & Ancient Near Eastern Cultures, The Sonia & Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University. The charcoal remnants were found in the archaeological excavation directed by Prof. Yosef Garfinkel of the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University. The findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports from the publishers of Nature.

‘Indisputable Proof of Domestication’

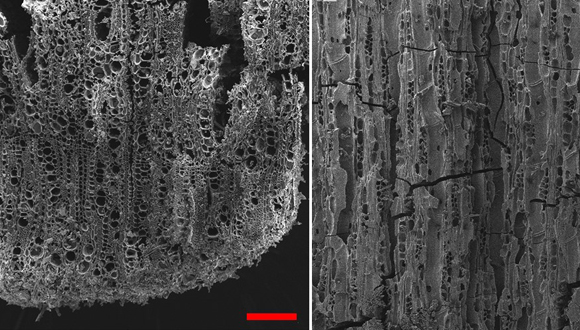

According to Dr. Langgut, Head of the Laboratory of Archaeobotany & Ancient Environments which specializes in microscopic identification of plant remains, “trees, even when burned down to charcoal, can be identified by their anatomic structure. Wood was the ‘plastic’ of the ancient world. It was used for construction, for making tools and furniture, and as a source of energy. That’s why identifying tree remnants found at archaeological sites, such as charcoal from hearths, is a key to understanding what kinds of trees grew in the natural environment at the time, and when humans began to cultivate fruit trees. »

In her lab, Dr. Langgut identified the charcoal from Tel Zaf as belonging to olive and fig trees. « Olive trees grow in the wild in the land of Israel, but they do not grow in the Jordan Valley, » she says. « This means that someone brought them there intentionally – took the knowledge and the plant itself to a place that is outside its natural habitat. In archaeobotany, this is considered indisputable proof of domestication, which means that we have here the earliest evidence of the olive’s domestication anywhere in the world.”

7,000 years-old microscopic remains of charred olive wood (Olea) recovered from Tel Tsaf (Photo: Dr. Dafna Langgut)

“I also identified many remnants of young fig branches. The fig tree did grow naturally in the Jordan Valley, but its branches had little value as either firewood or raw materials for tools or furniture, so people had no reason to gather large quantities and bring them to the village. Apparently, these fig branches resulted from pruning, a method still used today to increase the yield of fruit trees. »

Evidence of Luxury

The tree remnants examined by Dr. Langgut were collected by Prof. Yosef Garfinkel of the Hebrew University, who headed the dig at Tel Zaf. Prof. Garfinkel: « Tel Zaf was a large prehistoric village in the middle Jordan Valley south of Beit She’an, inhabited between 7,200 and 6,700 years ago. Large houses with courtyards were discovered at the site, each with several granaries for storing crops. Storage capacities were up to 20 times greater than any single family’s calorie consumption, so clearly these were caches for storing great wealth. The wealth of the village was manifested in the production of elaborate pottery, painted with remarkable skill. In addition, we found articles brought from afar: pottery of the Ubaid culture from Mesopotamia, obsidian from Anatolia, a copper awl from the Caucasus, and more. »

Dr. Langgut and Prof. Garfinkel were not surprised to discover that the inhabitants of Tel Zaf were the first in the world to intentionally grow olive and fig groves, since growing fruit trees is evidence of luxury, and this site is known to have been exceptionally wealthy.

Dr. Langgut: « The domestication of fruit trees is a process that takes many years, and therefore befits a society of plenty, rather than one that struggles to survive. Trees give fruit only 3-4 years after being planted. Since groves of fruit trees require a substantial initial investment, and then live on for a long time, they have great economic and social significance in terms of owning land and bequeathing it to future generations – procedures suggesting the beginnings of a complex society. Moreover, it’s quite possible that the residents of Tel Zaf traded in products derived from the fruit trees, such as olives, olive oil, and dried figs, which have a long shelf life. Such products may have enabled long-distance trade that led to the accumulation of material wealth, and possibly even taxation – initial steps in turning the locals into a society with a socio-economic hierarchy supported by an administrative system. »

Dr. Langgut concludes: « At the Tel Zaf archaeological site we found the first evidence in the world for the domestication of fruit trees, alongside some of the earliest stamps – suggesting the beginnings of administrative procedures. As a whole, the findings indicate wealth, and early steps toward the formation of a complex multilevel society, with the class of farmers supplemented by classes of clerks and merchants. »